MODEL BUSINESS MODEL – PART 4

…BECAUSE

IT WORKS ITS WAY INTO THE SOUL

Over the last few months, GW released an old favourite. It was a game from 1996 called Necromunda. A popular skirmish table-top game based on their Warhammer 40,000 setting, 2nd Edition, before all the big-ticket, cash grab and piss-poor rules changes that screwed the game for everyone. The appeal of that version of the hobby was small ‘squad’ sizes. It provided greater accessibility for players whose funds were limited. It got canned for that very reason.

So

along comes Armageddon, the new

version of Necromunda. It uses,

according to the forums discussing it, almost the exact format used by Necromunda. But it doesn’t use the old

Hive City and Outlander gangs. Instead, it uses ‘gangs’ formed from the

existing armies of Warhammer 40,000. Space Marines, Tau, Orks, Eldar, Necrons,

and so on. It saves GW from having to produce the old Necromunda ranges but allows all the older players to use models

that have sat idle for the better part of two decades.

Over the last few months, GW released an old favourite. It was a game from 1996 called Necromunda. A popular skirmish table-top game based on their Warhammer 40,000 setting, 2nd Edition, before all the big-ticket, cash grab and piss-poor rules changes that screwed the game for everyone. The appeal of that version of the hobby was small ‘squad’ sizes. It provided greater accessibility for players whose funds were limited. It got canned for that very reason.

GW

likes its sales to be big. A lot of cash in a single sale. The mindset of the

greedy is fairly predictable. They ditched the small sales because the

cost-profit ratio appeared small. But what smarter companies realise is that a

lot of small sales provides a lot of return. It caters to a broader market

base. Price them out of the market and suddenly you find your profits shrink

too, the smaller market base only purchasing a limited number of big ticket

items. Whoops.

It means players no longer have to spend thousands of dollars on models for Warhammer 40,000, some of which cost hundreds of dollars on their own. They can just use a dozen or so models. It seemed like a step in the right direction. Until you consider the cost of the Core Box with its rules, terrain, and enough models for two ‘gangs’. Another big-ticket item. It’ll set you back about AUD$279. That’s about half-a-week’s pay on minimum wage if you have a full-time job. GW didn’t think it through.

Or

did they? Disposable income for most people has become a mythical thing. Baby

Boomers often have it and tell fantastical stories about what things cost even

as they express confusion as to why the following generations cannot save. When

they were young, a house cost three year’s wages. They would go out to

restaurants and movies whenever they wanted. But now a house costs between

seven and twenty times annual wages, and eating out or going to movies is

limited to once or twice a year.

But

as utility costs and cost of living skyrockets, even the Baby Boomers are

starting to notice the bite. More of them, at least. This is something GW

appears to have ignored in its business strategy. Until you realise the average

person isn’t their target market. They are still focussing on the

over-privileged. People with more money than sense. The trolls that plague

their forums and once filled their stores. The really horrid people we were

glad got corralled in that community and hoped to God didn’t breed.

The

new version of Necromunda appears to

be a response to the success of Zombicide:

Black Plague and Zombicide: Green

Horde. Starved of a quick, fun game with great models and rules that are

not constantly changing and leaving entire armies unbalance, uncompetitive and

obsolete for years on end, players left GW in search of a better, less

expensive alternative. Among others, they found Zombicide. But how can they

compete with an AUD$160 Core Box when GW charges AUD$279 for theirs?

Well,

for a start, the Shadow War: Armageddon

Collection is sold for AUD$169 in the UK. But outside the UK things get

weird. GW marks up their prices when trading overseas. In the US it’s between

+25 to 30%. In Australia it’s a whopping +60 to 65%. And GW restricts internet

sales to its own site and gouges those markets in what appears to be legalised

Price Fixing that violates Fair Trade Agreements and Regulations. Those who

want the products have two choices: they can either not purchase GW product, or

they can keep bending over as they hand over cash and let GW fuck them up the arse.

Take their Shadow War: Armageddon Collection, for

example. In the UK it sells for GPB£100.

In Australia, however, the price is set at AUD$279. Given the Exchange Rate

(11/07/2017) is GPB£1.00 = AUD$1.69, the price should convert to

AUD$169. But for some inexplicable reason GW has added AUD$110 (GPB£65)

to the price, a mark-up of +65%. While the product does not appear to be sold

on the US section of their webstore, price comparisons on other products reveal

a similar pattern.

A Space Marine Tactical Squad of just ten tiny plastic figures sells

in the UK for GPB£25. But in

the US they sell for US$40 (GPB£31.09),

a 27.7% mark-up. In Australia it’s AUD$65 (GPB£38.4), a 53.6% mark-up. The Index Imperium 1 (the latest in a series of piss-poor Space Marine

Codexes) sells for GPB£15. In the

US it’s listed at US$25 (GPB£19.43), a

29.5% mark-up, and in Australia it’s listed at AUD$40 (GPB£23.65), a 57.7% mark-up. A Valkyrie sells in the UK for GPB£41. GW sells it in the US for US$66

(GPB£51.3), a 25.1% mark-up,

and in Australia for AUD$110 (GPB£65),

a 58.5% mark-up. What the fuck is that all about?

The

answer is obvious when you realise what’s going on. They aren’t competing on

price. GW and CMON are competing on culture. It took a while for me to see what

both were doing, and it left me feeling what can only be called disappointment.

The two companies have decided their money can be made by catering to the very

worst elements of their market: the trolls. That’s why they make no effort to

discourage them. They feed the rampant narcissism, greed, and pathetic

projection of that element of the community. The uncontrollable need to feel

important, to dominate others.

But

while CMON is attempting to break into the market, to carve out a chunk of

territory and claim it as their own, their interests only seem to be in

short-term, one-off bites. They seem relatively disinterested in maintaining

permanent customer loyalty. Their products are fully self-contained. No rule

updates. No supplements that also require constant updates. No need to gouge

their market by creating a system of built-in self-destruction where elements

become obsolete and subject to power-creep.

GW, on the other hand, has used those very practices for the better part

of two-and-a-half decades, indifferent to the unhappiness of the market,

comforted by the misapprehension losses will just be regenerated with the next

generation. Until the last decade or so, where they have responded to real

competition with legal action to crush rivals and get around price fixing and

fair-trade laws, a practice that sucks profit out at a slightly reduced rate

than what they’d suffer if they allowed competition to take root and retailers

to sell product without the dodgy restrictions imposed by GW.

This

year, we witnessed in awe one of the biggest take-down in corporate history.

The European Union’s competition watchdog bitch-slapped Google with an almost US$4.5B

penalty for breaching anti-trust rules with its online shopping service. In a

nutshell, Google used its market dominance to give itself what was an obvious,

and illegal, advantage. Meanwhile, its CEO, Sundar Pichai, received a pay-rise,

doubling his reimbursement to US$200M in cash and (mostly) shares.

What

is particularly interesting about this situation and decision is how similar it

is to the activities utilised by GW to maintain its tenuous grip on its market.

GW is founded upon the creative efforts of others, and despites this parasitic

practice, the company uses lawyers to lay claim to those ideas and limit

competition in order to use its market dominance (and in-house trade rules) to

give itself what an obvious, and illegal, advantage. And yet no real action has

been taken against them in response to this.

In the course of that finding against Google, it was noted that, no

matter how benign their intentions, the influence of large companies makes them

dangerous. In the hands of governments the internet is a tool used to shape the

attitudes of the people, promoting certain ideologies over others to provide

advantage to those controlling the ruling political party. Alternate political

movements can also use the internet to promote their agendas, and it’s not just

political parties.

All social constructs can make use of the internet to promote all

manner of ideas and stupidity. Religious extremists, anti-vaxers, climate

change opponents, and Trumplings. Their efforts reduce reality to nothing more

than paranoid, dystopian, “alternate facts” based “fake news”, terms that

reveal serious mental health issues affecting their supporters which they then

project on better educated people with claims it is their opponents who are

ignorant, bigoted, and insane, despite all the evidence to the contrary.

And then there are companies like Games

Workshop. A company that is founded not just on a parasitic premise that the

ideas of others are the property of GW, but a perverted culture of elitist,

anti-social behaviour that crosses the line into fascism. Where trolls are

encouraged and enabled, used to bully, insult, intimidate and silence all

opposition, and when they are betrayed, used up and shat out, the next generation

of mindless, half-wit sycophants replaces them.

The evidence is obvious. There’s twenty-five plus years of it. The

personality and lifestyle of Bryan Ansell himself, according to some sources,

is the very epitome of it. Warhammer and Warhammer 40,000 novels are filled

with the same. A post-apocalyptic society where Commissars and other

authorities murder those who dare to challenge, question, or otherwise fail to

obey the laws of the ruling elite. Just as with any literature, these stories

influence the cognitive development and personality of the reader.

Even those with a rudimentary education in psychology can see and

explain the dangers of an excessive exposure to a substance or culture:

addiction, assimilation, and a detrimental impact on the physical and mental

health of the subject. The addict will not stop with the negative behaviour

unless forced to do so. They cannot begin to recover until they admit they have

a problem. As long as they project their flaws on others, blame their victims,

and excuse or use disassociation to justify) their bad behaviour, they will continue

to be a practicing addict. GW and CMON uses this to sell product to their

market.

What

the worst element of their market wants is something that makes them feel

special, more important than those who do not have what they have. GW does this

by restricting access based on big-ticket prices, while CMON offers quantity at

a lower price but limits access to exclusive models to immediate backers. The

strategy seems suicidal from a maximising sales-profit point-of-view because it

makes no real sense. As the mock-interview with japester revealed, the attitude of these companies and their trolls is petty

and pathetic.

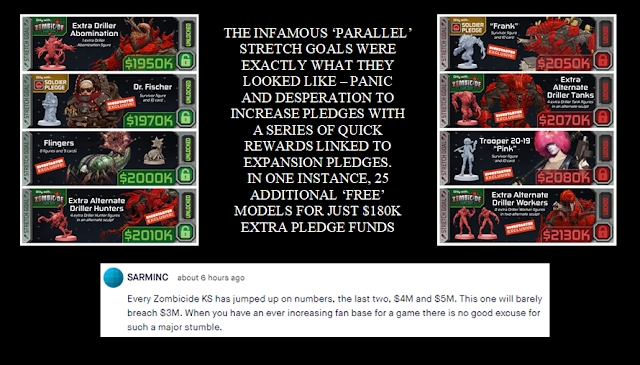

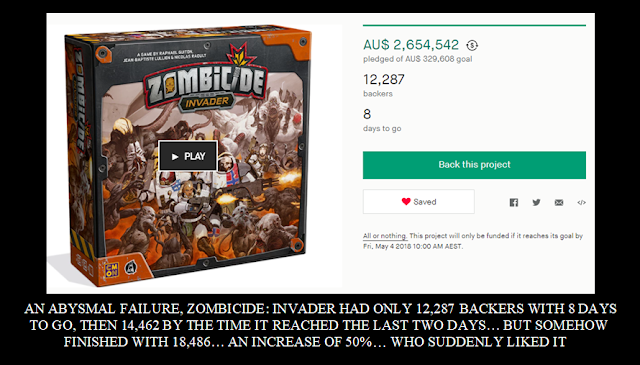

Let’s

have a look at the ‘logic’ behind the approach of CMON. They start a

Kickstarter project to fund the next game they produce. As an incentive they

offer Kickstarter Exclusives as Stretch Goals unlocked when a target is

reached. These are a ‘free’ addition to what the backer gets for a Horde

Pledge. They are not sold separately and not available to the general market.

They are a special toy awarded to (mostly) males between the ages of

twenty-and-forty for backing the project. Think about that. It gets worse.

According

to a ‘CMON kickstarter and exclusivity policies survey’ conducted by a guy

called Haposhi, the vast majority of the CMON community don’t have a problem

with exclusives being sold retail after projects are funded. And why would

they? They get the same models ‘free’ if they back the project with a Horde

Pledge (or purchase the applicable Optional Buy) where the rest of the market

would have to pay for them. But the ‘free’ notion is misleading.

Exclusives

are not free. Unless you purchase the applicable product, you do not get them.

And you most certainly don’t get them unless you backed the project and

(despite what CMON actually says in its policy) you only get them as part of

that pledge at that time. Worse, people who purchase the same product after it

goes retail are actually paying for the backers to get their ‘free’ toys. They

do not get them but pay the same price as a backer, effectively subsidising the

‘free’ toys the backers received.

The

trolls, of course, have no problem with this. They insist anybody who does not

agree with them being super special and more important than ordinary people is

those people being ‘salty whiners’ and ‘butt hurt’, a particularly vile remark

that is clearly projection given a greater analysis of their attitudes. Trolls

insist Haposhi’s survey was flawed because there were only about 1,800 subjects

but, more importantly, because it failed to provide evidence to support the

attitude of the trolls.

The

survey size of 1,800 was the equivalent of about 8% of the total number of

backers for Zombicide: Green Horde,

although it was conducted the year before and focussed on CMON rather than just

that game. The insistence that this group was too small to provide any real

insight was as idiotic as it was a reach to discredit the findings. If

anything, trolls would be over-represented due to their prevalence on

social-media sites where the survey was conducted, something that would present

over-inflated results favouring their view on the issue.

And

what a twisted result it was. The comments section beneath Haposhi’s findings

and conclusion only served to prove many of the points he made. About a quarter

of the respondents had indicated they would not buy the product retail if they

were aware of just how much more backers received, pointing out they were

receiving less content but apparently unaware that retail buyers were actually

paying for that ‘free’ content backers received. Still, the ‘free’ content

gifted to backers as an incentive to get people to back the project was having

a negative impact in the retail market.

registers.accc.gov.au/content/trimFile.phtml?trimFileTitle=D14+133026.pdf

It

made sense. Anybody who bothers to check prices on ebay for the exclusives

being on-sold by backers of Zombicide: Black

Plague will quickly realise the exclusives in the Core Box are raising

around $500. The Zombicide: Green Horde Core Box

includes around 55 exclusives that can be sold for around $10 each (or, in some

cases, as much as $40). Even if those backers sell the Core Box for just $110

(a loss of $50), they make $500 from this lucrative black market because of

CMON’s exclusives policy.

Assuming

just 5% of the backers of Zombicide:

Green Horde do the same, that’s half-a-million dollars in lost revenue. And

that’s a conservative figure. Now, assuming there are at least five bidders on

each item being sold-on, and CMON were to sell the same items retail for just

half what scalpers are getting (say $5 each), that’s $1.25M in lost trade. CMON

has completed about 40 projects, so if they squandered just $½M in sales on

each, that’s about $20M in untapped revenue! Again, these figures are

conservative.

CMON

has also linked at least two of their games (Massive Darkness and Zombicide:

Green Horde) with miniatures and cards, creating a demand by providing game

content that can be used in each. This tactic creates an incentive for backers

to fund the other project in order to access that content, especially if the

content is exclusive. But, again, it’s entirely plausible that more people

might invest in the games if they had greater choice in what they could access

for purchase at retail.

registers.accc.gov.au/content/trimFile.phtml?trimFileTitle=D14+133026.pdf

Yes,

there is the inherent risk that you may produce an excess supply of stock that

does not sell because demand peters out. You may have to sell it at cost to

make your money back. You may take a loss. But if you already use Kickstarter

as a platform, why not use it to raise capital and guarantee sales for extended

production? Pick a core project component, like an Expansion (a real one) for

the game, add Option Buys, limit exclusive Stretch Goal incentives, and have at

it every few months.

But

what makes this situation even more irksome is the simple fact that players who

lose or break any of the components for their game cannot purchase replacement

parts because of that idiotic policy. Despite the fact that retail market would

be paying for exclusives that the backers get for ‘free’ for their pledge,

about 10% of the respondents in Haposhi’s survey insisted they would not back

the project if they knew exclusives would be available for retail sale. Now

that’s pretty damn petty.

The

very same people who levelled vindictive insults at people who wanted to

purchase game content provided to backers were now threatening to throw an

almighty tantrum if non-backers were given access to exclusive game content at

the retail level. In reality, they would snivel and whine about it even as they

went back on their threat, backed the project, and tried to feel special

because their copy included the same items at no additional cost to them.

registers.accc.gov.au/content/trimFile.phtml?trimFileTitle=D14+133026.pdf

This

situation is insane. Trolls are complaining and bullying people over plastic

toys worth only a few cents to produce and use in a game. A child’s game. A

bunch of (mostly) males in their twenties-to-forties using what can only be

considered an idiotic policy on the accessibility of exclusive game content to

act like they are special, more important than others, and bully other people

with insults that are clearly the projection of their own very flawed

personality problems. Grow the fuck up.

Seriously,

what is wrong with you people?! You are too old to go online where you inflict

your incredibly stupid attitudes on others. You are definitely too old to go

into a hobby store, try to claim it as your own personal kingdom, and attempt

to dominate children. It’s creepy. The only benefit is that you being online

restricts your presence in the real world, and a store serves as a cage for a

similar benefit. It’s no wonder women avoid you. The rest of the world is

grateful your behaviour limits your ability to breed more idiots, but if you

could just piss off and shut-up altogether, the world would be a better place.

However,

back to the survey. It did indicate one very real, very legitimate market

backlash. One far more damaging to potential profits than the empty, snivelling

threats of trolls. Many potential retail customers feel cheated by just how

much game content backers get, while they do not, and would not purchase the

product as a result. Worse, even if this additional game content were available

at retail, having to pay for what backers got free was considered, by many, to

be a deterrent.

registers.accc.gov.au/content/trimFile.phtml?trimFileTitle=D14+133026.pdf

The

trolls, of course, refer to retail customers who (rightfully) feel cheated, and

used to supplement what backers get, as ‘butt hurt’, as if it is their right to

have others pay for the entitled attitude of trolls. This is a huge deterrent

to potential customers. As word spreads, the lack of game content, plus the

elitist and baffling attacks by half-wit trolls, this policy negatively impacts

upon sales and profits. And then there are the motives of the backers

themselves.

The

impression of all that support the game is that the game is popular, that

people want the products to play the games. That’s not entirely true. Some of

the backers don’t buy into the elitist troll culture CMON fosters. The game

itself doesn’t have as much appeal as a game but the investment in an on-sale

market, the possibility to make as much as AUD$750 by trading the AUD$160 (plus

P&H) content of the Core Box to those who missed the Kickstarter. It would

make sense, then, for CMON to modify this, to adapt the exclusives policy to

the market.

The

simplest solution is middle-ground. Backers still get ‘free’ game content

classified as being ‘Kickstarter Exclusive’ because they get it as an

incentive-reward at established Stretch Goals. Those who purchase the same

items at retail would pay retail prices for them. But to limit the retail

backlash, exclusive content could be limited to around $100 worth of product,

with backers then offered ‘discount’ game content as a reward for Stretch Goals

beyond this limit.

registers.accc.gov.au/content/trimFile.phtml?trimFileTitle=D14+133026.pdf

If

the retail price were attached to the Kickstarter Exclusives, then backers

could select which ‘free’ reward they wanted during the pledge manager, and

which Stretch Goal ‘discount’ Optional Buys they would like to access. Yes, it

may seem a little confusing at first, but backers will figure it out. Yes,

trolls will cry about the sudden absence of feeling super special and being

able to post and say idiotic things about others as they project their worst

personality flaws onto their victims, but that’s their problem.

In

business, it pays to remember the moral of the story of the tortoise and the

hare: you snooze, you lose. CMON has an

opportunity here. They can continue to price and alienate potential clients out

of the market or they can embrace an opportunity to increase market share and

profit. Seriously, if someone says “me and the lads like what you’re making,

we’d like to give you $1.25M for your product,” are you going to say “no”? Are

you going to let trolls chase that money away? CMON does. So does GW.

GW boast that it does not do market research. It

dictates what the market wants. It refuses to adapt when this attitude proves

disastrous. Instead, it simply increases prices to gouge the contracted element

of its market that remains. It discards affordable product and focusses only on

big-ticket items, catering to that cashed-up, over-privileged, sociopathic

element. Every year, that element shrinks, and GW repeats the process, like the

ocean wearing away at a spur of former cliff, cut off from the now distant

shoreline and surrounded by relentless waves, wearing it away until it collapses.

And when it does, a tide of new life will descend upon the wreckage,

picking over what remains as they stake out a claim to territory and resources.

It is an ongoing process. Even now, CMON helps several of these emerging

companies take advantage of the spaces abandoned and discarded by GW. Idiotic

legal actions have only hastened the end, not delayed it. Perception, it is

said, is reality. Perception only lasts so long as it is based in reality and

promoted by likeable personalities. Not trolls.

How long a company lasts depends upon how well

they learn and implement the lessons of marketing. This is the ultimate test

for any business. How it is remembered. If it is recorded for all the good it

did, all the hope and joy it inspired, or with uncompromising hatred and savage

glee. When (not if) a company like GW finally collapses and is no more, it will

not be mourned. Instead, someone will grin and say, “so this is how it dies…

not with a whimper, not with sorrow, but to the sound of thunderous applause.”

Comments

Post a Comment